Epiphanies one after another, but intimately linked, describe yesterday and this morning too, but in this final blog from Viet Nam, I offer you yesterday as it resonates today.

Psychologists! You might think of those who inhabit the realms of armchairs and academia, but yesterday such inhabitants rose from their armchairs and thawed academia.  Dr. Hao, Deputy Director of the Institute for Cross-Cultural Psychology, welcomed Ed, Barbara, Song and me with grace and warmth, as we met with three women on the faculty of the Institute . Each of these women had known losses of loved ones in the American War. With Dr. Hao as facilitator, we shared stories of personal history and current perspectives. The stories formed the common thread.

Dr. Hao, Deputy Director of the Institute for Cross-Cultural Psychology, welcomed Ed, Barbara, Song and me with grace and warmth, as we met with three women on the faculty of the Institute . Each of these women had known losses of loved ones in the American War. With Dr. Hao as facilitator, we shared stories of personal history and current perspectives. The stories formed the common thread.

Dr. Hoa practices social psychology with Dr. Hao and is a native of Quang Tri City. In 1970, when she was just seven years old, she lost her father in the American War. He was killed just 10 miles from An Loi, where my first husband, Russ, lost his life two years earlier. In 1973, the relics of her father were found and brought to the war memorials of their village. Their family received from the government a “ticket of morals”. Four members of her grandmother’s family lost their lives in that war. Her grandmother received the title of “Heroine Mother’. Such sacrifice brought honor from their government. Then there was Dr. Huyen, only 40 years old. At the age of five months, she and her three-year-old sister lost their father. It was 1979. He had survived the American War, but not the war of resistance against China, which invaded Viet Nam not long after the end of the American War and which Viet Nam ultimately resisted. Dr. Khanh’s story is more complicated. A half-bother had fought in the American War with the ARVN/American allies in the South) and was killed. Two sisters joined the National Liberation Front (aka Viet Cong). Her father went north and fought with the NVA. “How did you go about loving them,” I asked. “I loved them all,” was her reply.

Dr. Hoa practices social psychology with Dr. Hao and is a native of Quang Tri City. In 1970, when she was just seven years old, she lost her father in the American War. He was killed just 10 miles from An Loi, where my first husband, Russ, lost his life two years earlier. In 1973, the relics of her father were found and brought to the war memorials of their village. Their family received from the government a “ticket of morals”. Four members of her grandmother’s family lost their lives in that war. Her grandmother received the title of “Heroine Mother’. Such sacrifice brought honor from their government. Then there was Dr. Huyen, only 40 years old. At the age of five months, she and her three-year-old sister lost their father. It was 1979. He had survived the American War, but not the war of resistance against China, which invaded Viet Nam not long after the end of the American War and which Viet Nam ultimately resisted. Dr. Khanh’s story is more complicated. A half-bother had fought in the American War with the ARVN/American allies in the South) and was killed. Two sisters joined the National Liberation Front (aka Viet Cong). Her father went north and fought with the NVA. “How did you go about loving them,” I asked. “I loved them all,” was her reply.

Time for a visit with one of Viet Nam’s most revered poets: Colonel Hung. Yes, he’s a colonel in the Vietnamese army and an internationally celebrated poet in Luc Bat, meaning six-eight. It’s a poetic form of lines alternating between six and eight syllables—or words, since Vietnamese is a monosyllabic language. In each six-eight coupling, the rhyming occurs at the sixth syllable of each line. A bit more challenging than haiku, yes? Song translated for us, and when we asked Colonel Hung to recite (via Song) one of his poems, he offered his poem of the day! Ed then took Song’s translation and morphed it into an English more-or-less Luc Bat form! Also present for this conversation was Thai Minh Chau, a journalist who writes for a women’s magazine and was working with Colonel Hung on a prospective article. I declined to ask why two men were authoring an article for a women’s magazine. Once in a rare while, I choose diplomacy over raised eyebrows!

Time for a visit with one of Viet Nam’s most revered poets: Colonel Hung. Yes, he’s a colonel in the Vietnamese army and an internationally celebrated poet in Luc Bat, meaning six-eight. It’s a poetic form of lines alternating between six and eight syllables—or words, since Vietnamese is a monosyllabic language. In each six-eight coupling, the rhyming occurs at the sixth syllable of each line. A bit more challenging than haiku, yes? Song translated for us, and when we asked Colonel Hung to recite (via Song) one of his poems, he offered his poem of the day! Ed then took Song’s translation and morphed it into an English more-or-less Luc Bat form! Also present for this conversation was Thai Minh Chau, a journalist who writes for a women’s magazine and was working with Colonel Hung on a prospective article. I declined to ask why two men were authoring an article for a women’s magazine. Once in a rare while, I choose diplomacy over raised eyebrows!

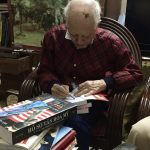

Capping t he day was a visit with Huu Ngoc in the home in which he and his wife have lived longer than most of us have been alive. This 100-year-old scholar, linguist, poet, and author of 43 books (working on his last!) greeted us warmly, speaking perfect English and accompanied by his assistant, Nguyen Viet Dung (76 and not too old to be his son!). We sat for well over an hour drinking in the seasoned wisdom of this man fondly known as Thay (revered teacher).

he day was a visit with Huu Ngoc in the home in which he and his wife have lived longer than most of us have been alive. This 100-year-old scholar, linguist, poet, and author of 43 books (working on his last!) greeted us warmly, speaking perfect English and accompanied by his assistant, Nguyen Viet Dung (76 and not too old to be his son!). We sat for well over an hour drinking in the seasoned wisdom of this man fondly known as Thay (revered teacher).  Does Thay have a magnum opus? Perhaps, and it would surely be Wandering Through Vietnamese Culture (2004), a 1200-page tome that delivers far more than its title indicates. After Viet Nam successfully resisted the invasions of Japan, China, France, and America, Huu Ngoc authored a book on that country’s culture as “a means to humanize the former enemy.”

Does Thay have a magnum opus? Perhaps, and it would surely be Wandering Through Vietnamese Culture (2004), a 1200-page tome that delivers far more than its title indicates. After Viet Nam successfully resisted the invasions of Japan, China, France, and America, Huu Ngoc authored a book on that country’s culture as “a means to humanize the former enemy.”  After 1975, for example, he wrote A File on America as a means of facilitating Vietnamese and American friendship. What is America for him? “Idealism and pragmatism.” As for his current perspective on his own country? “Viet Nam is now engaged in its most difficult war, the war to save its own soul.” The materialism that commonly accompanies Western capitalism is undermining values and traditions that have sustained Vietnamese culture for millennia. His counsel for us all? “Look for happiness in the spirit, in serenity.”

After 1975, for example, he wrote A File on America as a means of facilitating Vietnamese and American friendship. What is America for him? “Idealism and pragmatism.” As for his current perspective on his own country? “Viet Nam is now engaged in its most difficult war, the war to save its own soul.” The materialism that commonly accompanies Western capitalism is undermining values and traditions that have sustained Vietnamese culture for millennia. His counsel for us all? “Look for happiness in the spirit, in serenity.”

Happiness, serenity, and generosity pour forth from this revered teacher and beloved “lion of literature”, as he is often referred to in Viet Nam. In a nearby pile of books—and books were piled high nearby—were some copies of his newest

Happiness, serenity, and generosity pour forth from this revered teacher and beloved “lion of literature”, as he is often referred to in Viet Nam. In a nearby pile of books—and books were piled high nearby—were some copies of his newest  work, Viet Nam: Tradition and Change. Huu Ngoc insisted that we each take a copy as his gift to us, and he graciously inscribed each copy. When I open its pages, I will be sitting again in the sacred space of this man who has stretched minds and opened hearts across history’s vacillation between war and peace, enmity and friendship.

work, Viet Nam: Tradition and Change. Huu Ngoc insisted that we each take a copy as his gift to us, and he graciously inscribed each copy. When I open its pages, I will be sitting again in the sacred space of this man who has stretched minds and opened hearts across history’s vacillation between war and peace, enmity and friendship.

I write on this last day in a land that has found its sustenance again and again in adaptation to change with community as its core. Surfacing for me is the Sioux word, tiospaye, “the people with whom one lives”. In Viet Nam, the people with whom one lives rise from the land that gives life, and the land that gives life nurtures the root structure of the people with whom one lives. This land and its people will live in me for as long as I live.

the land that gives life, and the land that gives life nurtures the root structure of the people with whom one lives. This land and its people will live in me for as long as I live.

Love and Hoa Binh and Good Morning, Viet Nam!

Jan